I went to Mississippi to escape reality.

There was no other reason.

My friend of 30 years had gotten fed up to the quitting point with a job in the human services industry. In fact, both of us had spent most of our careers in the service of others. Lately, a newly-discovered love of all things “data” had taken over the human element. Her bosses wished to know why it took so long for the ER’s only night-shift tech to complete CAT scans for all who needed them. Signing reports with the phrase, “The only tech on duty,” didn’t avail much. Meanwhile, on my watch, students sat for hours waiting for other students to complete state standardized tests. It’s a validated world, and if you aren’t rolling in the right numbers, they’ll close the house on you like a shark in Vegas.

Or wherever you find yourself.

I wasn’t sure if I wanted a do-over or if I wanted to burn my bridges Norma Ray style, but over coffee, the tech from Illinois and the teacher from Tennessee decided to go to The River. I decided I wanted to capture the Big Daddy in some way I hadn’t before.

Not that I hadn’t tried. There’s a photo of me on a river boat, the Delta Queen, when I was twelve. I have just bragged to my dad that I’ve been to the Coast of Arkansas, as if there is such a thing. I have only just touched the yellow sand on the west bank of the Mississippi at Memphis. You would think I had crossed the Jordan from the fuss I make. In the photo, the rest of the family has left to hear a band. I’m alone on the lonely side of the boat, and my dad snaps the picture. I manage a smile, but there’s something sobering about this river. You don’t come to the river lightly the way you run down the beach at Gulf Shores.

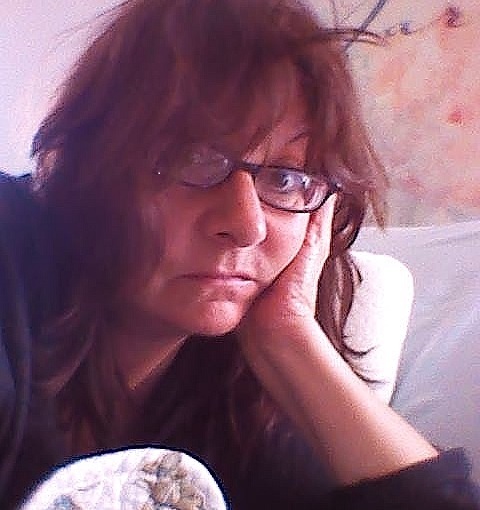

This time, I’m decades older, and I really don’t have a plan.

This time, it’s Natchez.

We pull in just on evening after driving through halls of twisting vines and Spanish moss. If you didn’t know you were on U.S. 28, you would think you had made a wrong turn into Guatemala. The dark highway spits us out on the Natchez Trace just above the point where it becomes Devereaux Street. We pass by Highway 552. I don’t tell my friend that I wrote a whole world of crime fiction back in 2010, most of which occurs on that road. The GPS voice harps that our turn is coming up. I almost believe I could tell my friend to turn around, maybe the Tharpes are home, we should maybe talk about the murder, maybe somebody made gumbo tonight. Instead we turn in the parking lot at the Natchez Grand Hotel, get checked in, and head down, like everybody else, to Silver Street.

It’s the oldest part of town, where riverboats once brought gamblers and the lawless looking to raise funds for further travel or maybe a more comfortable bed. Everyone, from Spanish missionaries to Jesse James, stayed on Silver Street at one time or another. We stop into Magnolia Grill and have to wait forty-five minutes for a table. Not for the last time, we order oysters Bienville, but I know twilight is coming, and like everyone else, I want to capture the River.

At first, there’s a pink pillar of cloud just over the water about mid-way. This begins a moment-by-moment change in gradation of color until the mist starts building, obscuring the view of the bridge joining Natchez to Vidalia, Louisiana. Vidalia is a little town like you’d find anywhere except with Crawfish. The shift in color continues until the atmosphere is rendered platinum, the same color as the bridge. For a while, you can’t see the bridge for the murk. When it’s almost too dark, I snap a few photos.

This murky darkness with only a ball of fire for light brings everyone out of the restaurant. It’s as if we’ve all lost our minds and decided to dance in the last of the pink light. Like we’re thinking maybe the ball of fire will sink into the platinum water for the last time. The people standing on either side of me don’t speak English. One group is from Poland, another from Japan. I am native to the river but from much farther upstream. We have all come here looking for something in the gray murk. We have unspoken questions. If the River answers, we are sworn to secrecy.

Rapidly, I realize I’m experiencing an eclipse. The bridge is a heavenly body; the River is the Sun, and it’s fading, stealing away its own light and leaving a monochrome dream. Even the tourists are quiet now. We can’t even see each other. What sound not swallowed in mist is dwarfed by a strange river high-tide and the breeze in the poplars.

There is no way of measuring this experience, and I don’t want to. I don’t want to hear the statistics on flooding or the number of riverboats, tug boats, or barges on any given day. I don’t want even the scent of validation. I have learned in brutal ways that validation is overrated and possibly not even a real thing. Some ways you look at this River, it is an illusion. At twilight, you have to accept it on blind faith. You feel through the mist for it, like groping to get your life back.